Blogs

Town of New Castle

How We Got Here: A Brief History of New Castle

The First Inhabitants

Humans began to arrive in this region after the final departure of the glaciers, about 10,500 BCE. At first nomadic, over the millennia they became more settled, living in seasonal villages. They were primarily hunter-gatherers but also occasional farmers. In Westchester, they congregated at certain seasons along the Hudson River and Long Island Sound to fish and harvest shellfish. Inland, they engaged in slash-and-burn agriculture, temporarily clearing fields and raising crops such as the Three Sisters (corn, beans, and pumpkins). Those in this immediate area belonged to the Wappinger tribes and spoke dialects of the Algonquin language that was prevalent along much of the eastern coast of North America.

Once European settlement began in the early 1600s, conflict with the Native Americans became inevitable. Open war broke out in the 1640s, and they were brutally suppressed. European diseases such as smallpox took an even greater toll. By the time New Castle was settled in the early 1700s, there were almost no Native Americans left.

The Colonial Period

The shape of New Castle was largely set by the end of the 17th century when the Philipse and Cortlandt manors were established to the west and north, and the town of Bedford to the east. The triangular wedge of land in between would eventually become the core of the town.

Throughout the Colonial Period, New Castle was simply the northernmost part of the town of North Castle and was carved out of a royal land grant called the West Patent, issued to Caleb Heathcote and nine other partners in 1702.

New Castle was first settled in the early 1730s. Most of the pioneers were Quakers from Long Island or Connecticut, but some were Episcopalians, Presbyterians, or other Protestants. The original one-room Quaker Meetinghouse was built in “Shapequa” in 1754, and St George’s Episcopalian church in what is now Mt. Kisco, in 1761.

The homes of the early settlers were quite small, usually just one or two rooms plus an attic loft for sleeping and storage. Some were clustered near the meetinghouse or church, but most were on widely scattered farms. The few stores were similarly scattered, and craftsmen such as blacksmiths, carpenters, and shoemakers worked out of their homes. The only significant industries were grist mills and sawmills — essential facilities even in wilderness communities.

Progress abruptly halted with the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. After the Battle of White Plains in 1776, the Quaker meetinghouse and St. George’s served briefly as field hospitals for Washington’s wounded soldiers. New Castle then became part of the so-called Neutral Ground of Westchester, not formally occupied by either Patriots or Loyalists, but suffering attacks from both. The Quakers were caught in the middle — their pacifism forbade them from taking sides in the conflict.

New Castle in the New Nation

New Castle soon recovered from the war. New homes were built, larger and more comfortable than before. New roads were laid out, including a major turnpike extending from Ossining to Somers (now Routes 133 and 100). Most important of all, the Town of New Castle achieved its own independence in 1791, when it became formally separated from North Castle.

The economy was composed mainly of self-sufficient subsistence farms that engaged in only limited trade with outside markets. Most of the inhabitants were still Quakers. In 1828, there occurred a schism between Quaker factions called the Hicksites and the Orthodox. In Chappaqua, the Hicksites remained at the original meetinghouse, while the Orthodox constructed a second meetinghouse at the northern end of the graveyard.

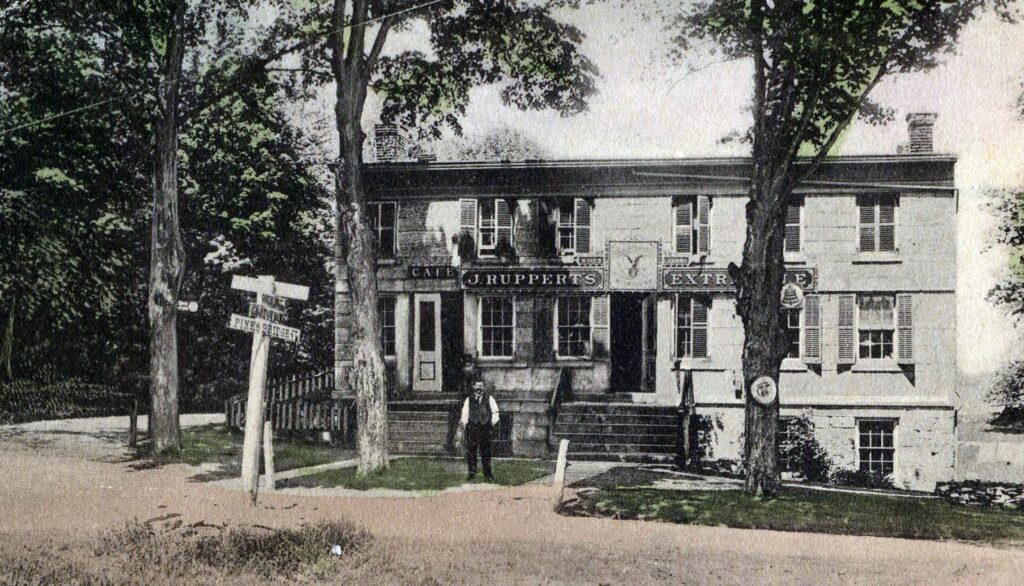

About 1817, an inn and tavern on the new Somerstown turnpike was rebuilt in massive blocks of stone. The Granite House became the birthplace of a new hamlet that one day would be called Millwood.

An important development was the establishment of a statewide system of public schools, tax-supported and locally supervised. Each New Castle district had a one-or-two-room school for local students. The basic education provided by these “common” schools was all that most students received for over more than a century.

The Railroad Revolution

By 1846, construction of the New York and Harlem River Railroad extended from the city into Westchester as far as Chappaqua. The arrival of the railroad produced sweeping and permanent change.

Previously, Chappaqua had been loosely centered around the Quaker meetinghouse. Now it became concentrated in a new village at the railroad crossing. Chappaqua became the predominant community in New Castle from that time on.

The railroad completely transformed the local economy. Agricultural produce could now reach markets in New York City in hours rather than weeks. The shift from subsistence farms to market farms was rapid and revolutionary. In the rocky, hilly ground of New Castle, two kinds of market farming proved especially rewarding: dairying and fruit production – particularly of apples.

Milk production and distribution became a major local industry. Local dairy farmers would milk their cows at dawn and deliver the milk in cans to the railroad station in time for an early train to the city. The empty cans would be sent back in the evening, and the process would be repeated.

Apple orchards, like pastures, required neither extensive tilling nor level ground. The best apples would be shipped to the city for fresh eating. Those with relatively minor blemishes would be pressed for cider. The rest could be fed to livestock.

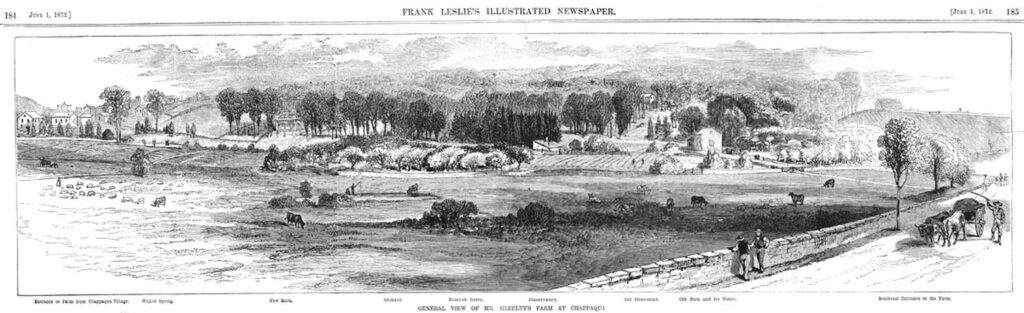

Ready access to the city by train also began to attract a new kind of resident — affluent New Yorkers seeking a healthful country home for their families. One of the first of these was Horace Greeley. From 1852 to 1854, he bought 78 acres of open land near Main Street, now King Street and Bedford Road, to serve not only as his summer home but also for his experiments in farming.

Declining Farms, Growing Hamlets, and Rising Industries

Throughout the 1800s, New Castle remained predominantly rural, but in the decades after the Civil War, agriculture gradually became less profitable, and the number of farms declined. The principal cause was the national expansion of the railroads, bringing increased competition from other parts of the country.

At the same time, though, the business center in Chappaqua steadily grew. The arrival of a second railroad in western New Castle resulted in the development of a whole new hamlet. And the formation of genuine industries provided fresh opportunities for local employment.

Before the New York and Northern Railroad (later the Putnam Division of the New York Central) was extended through New Castle, there was no real community in the western half of town. Its most significant building was the Granite House inn and tavern, serving travelers on the Somerstown Turnpike. The neighborhood was called Sarles Corners and then Merritt’s Corners, after the proprietors of the inn.

Once a station stop on the railroad was created near Merritt’s Corners in 1881, homes and businesses sprang up around it. The new hamlet came to be called Millwood. Though never as large and populous as Chappaqua, it soon achieved a distinct identity of its own.

The rise of local industries helped compensate for the decline in agriculture. The largest by far was the Spencer Optical Manufacturing Company in what is now Mt. Kisco. From 1874 to 1888, it was one of the country’s leading producers of eyeglasses. Downtown Chappaqua featured a shoe factory and a pickle factory on North Greeley Avenue, and a barrel factory on Hunts Lane. At the end of Hardscrabble Road was a steam cider mill and vinegar factory, and in Millwood, ice from Echo Lake was commercially cut, stored, and shipped.

The Hilltoppers

As agriculture became less profitable, more and more local farmers became inclined to sell and move out. There were also more potential buyers – wealthy New York City businessmen seeking to acquire country estates. They were familiarly known as “hilltoppers,” for they often chose to locate their mansions on high ground with long vistas. They not only occupied a substantial portion of the town, but also brought additional prosperity.

The estate era climaxed in the first decades of the 20th century. The Great Depression brought it to an end, along with many of the fortunes that had produced it. Most of the former mansions are gone, leaving behind only scattered outbuildings, often transformed into suburban homes.

New Castle Turns Suburban

By the early 1900s, trolleys, elevated trains, and subways made all parts of New York City accessible from Grand Central Station, and daily commuting to the city became both practical and attractive. New Castle, and Chappaqua in particular, shifted from rural to suburban. Developers and builders bought up former farms and estates and subdivided the land into residential neighborhoods. As new homes became available, the population shot up, almost doubling by 1930.

The earliest residential subdivisions were composed of relatively small lots, concentrated near the railroad stations. As automobiles became more common, developments with larger lots were created outside these central clusters. The pattern became formalized with the passage of the first zoning law in 1928.

Population growth was accompanied by an expansion of the public school system. The network of small common school districts was consolidated into a single central school district, climaxing in 1928 with the construction of the comprehensive Horace Greeley School (now the Robert E. Bell Middle School).

The railroad through Chappaqua was substantially upgraded. A new and much larger passenger station was dedicated in1902, on land donated by Horace Greeley’s daughter Gabrielle Greeley Clendenin. At about the same time, the single track became two, greatly increasing the number of trains on the line. In 1930, the ground-level railroad crossing was replaced by a new bridge.

Bust, Boom, and Beyond

New Castle weathered the Depression better than many other parts of the country. Suburban growth slowed but did not end. Public works projects helped mitigate the slump. The Taconic Parkway was completed through Millwood in 1932, and the Saw Mill River Parkway was extended as far as Chappaqua in 1934. In 1939, Federal support made possible a major enlargement of the Horace Greeley School.

The Lawrence family of developers had planned in 1929 to develop a whole new village on property they owned next to Lawrence Farms South. The Depression caused the Lawrences to delay and then abandon these plans, and in 1936 they sold the property to the Reader’s Digest Association, which completed its iconic headquarters building in 1939.

World War II, when most construction was diverted to the war effort, also hindered growth. But in the following decades, new home building and increased population raced ahead hand in hand, reaching a peak about 1970, and have continued ever since.

As before, population growth was accompanied by an expansion of the school system. The postwar explosion necessitated the construction of three new elementary schools, Roaring Brook in 1951, Douglas Grafflin in 1962, and Westorchard in 1971. The separate Horace Greeley High School was built in 1957, requiring the older school to be renamed the Robert E. Bell Middle School. And finally, a second middle school, Seven Bridges, was built in 2003. At each stage, the curriculum became more sophisticated and demanding, contributing to Chappaqua’s reputation for educational excellence. And, of course, the more the schools improved, the more the district attracted families to move here.

Rising costs, rising demand, and zoning restrictions all contributed to a pattern of growth that continues to the present – larger houses, on larger lots, further from the commercial centers. There was virtually no multifamily housing until a court decision in 1979 forced a revision of the zoning code. Recently, Federal and state mandates have forced the construction of the town’s first multistory, multi-unit apartment building, with income restrictions for tenants.

INFO

Shipping & Returns

Financial Disclosures

The New Castle Historical Society follows all current CDC protocols.

The Museum and grounds are handicapped accessible.

LOCATION

HOURS

Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday from 11 am – 3 pm.

Or by appointment: president@newcastlehs.org

laws of the State of New York. All donations made directly to New Castle Historical Society are tax-deductible to the extent allowed by law.

©2025 New Castle Historical Society | All Rights Reserved Privacy Policy